Accuracy, Precision and Noise of Gas Sensors – Definitions

Introduction

„Accuracy“ is one of the most important quality criteria of a gas sensor. But sometimes „precision“ rather than „accuracy“ is required for sensors. And unfortunately, in practice, high measurement accuracy often has to be bought at the price of reduced precision and vice versa.

Data sheets often fail to declare what is actually meant by accuracy and precision. For example, „signal resolution“ is often simply declared as accuracy, which is definitely not correct in most cases.

And to make matters even more complicated: the measured value displayed on the sensor reading is limited by the „signal resolution“ and „sensitivity“ of the sensor.

On the other hand, the above terms are defined slightly differently in different areas of application.

This article aims to avoid misunderstandings: In the following, the terms are defined. In a following article examples are given to show in which applications „accuracy“ is required and where „precision“ is needed.

Important terms

Accuracy

Accuracy

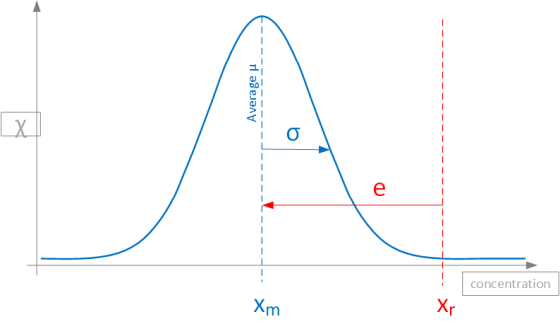

Accuracy refers to how close a measurement of the concentration is to the real gas concentration (definition according to ISO 5725–1 [2]). The error e = | xm – xr | denotes the distance between the measured value xm and the real value xr . A high measurement accuracy means a small error e.

Precision

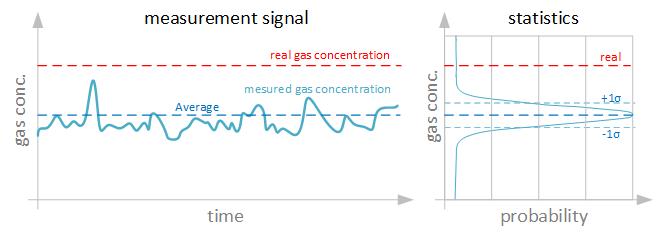

As every measurement is subject to a certain degree of randomness, several measurements of the same gas mixture carried out in quick succession will have slight measurement deviations. This is also referred to as noise xnoise of the sensor. If these deviations are purely random and independent of other measured variables, these measured values will have a statistical Gaussian distribution around the mean value μ. If the repetitive measurements are close to each other, this is referred to as high precision or, conversely, low noise xnoise

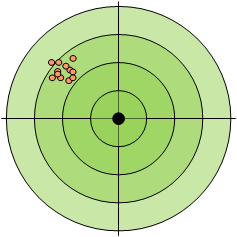

High precision, low accuracy:

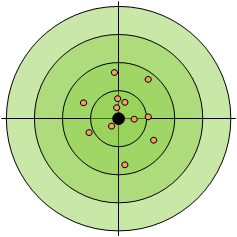

High accuracy, low precision:

Noise

Noise is defined as random fluctuation of the measurement signal. This is mainly induced by random quantum effects such as thermal noise (Johnson-Noise) in electrical resistors or EMI disturbances.

The noise xnoise is defined as the 1σ width in the Gaussian distribution Χ of all measured values of a real quantity xr, corresponding to the statistical standard deviation of the measured values x around the mean value xm (for Johnson-Noise).

Detail of the probability distribution χ of a noisy signal around the mean value xm in relation to the real concentration xr with the measurement error e:

Sensitivity and Resolution

Sensitivity

The term Sensitivity S of a physical sensors refers to the slope of the sensor output y in relation to the measured physical parameter change x (dy/dx). So for example if a change of gas concentration of 10’000 ppm will induce a voltage change in the sensor of 1 volt there will be a sensitivty of 1/(10’000) = 1E‑4 V/ppm.

Internal Digital Resolution

Internal Digital Resolution is specified as the smallest detectable incremental change of the sensor signal. This is limited by the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) bit resolution and the sensitivity S.

For example if the sensor above with a sensitivity S = 1E‑4 V/ppm is sampled with an 16-bit ADC, a internal signal resolution of 6.5 digit/ppm will result, or 0.15 ppm/digit resolution.

Displayed Reading Resolution

The display resolution is defined by the full-scale-range (FSR) scaling and the displayed smallest unit of physical change displayed. A high resolution means small changes of gases can be displayed.

For example, if the digital output of the display is scaled to show the gas concentration in % (instead of ppm) and the display shows two decimal places, the display resolution is Δc = 0.01% gas concentration, which is much larger than the internal signal resolution of the example above.

Detection Limit

The limit of detection (LOD) is defined as the lowest concentration change of a gas which reliably can be detected or extracted from the measurement signal.

In a signal with Guassian noise, the statistical confidence for a measured value is given by:

±1‑σ: 67% confidence

±2‑σ: 95% confidence

±3‑σ: 99.7% confidence

Example:

The gas concentration reading shows 1000 ppm based on a signal which has a noise-level of 1‑σ = 10 ppm: In 99.7% of all readings the effective gas concentration will be within 970 – 1030 ppm (±3σ).

Improving the Dectection Limit by Averaging

The LOD can be improved by averaging the noisy measurement signal. In a Gaussian noise signal, the LOD improves by the square-root of the averaged data points.

Example:

Averaging the signal over 4 consecutive measurements will improve noise by a factor 2 as well as the lower limit of detectivity.

The limit of improving the detectivity is given by systematic errors such as thermal drift and is very well displayed in a Allan-Variance diagram [3].

Example:

Same signal as above, but with moving averaged of N=16 samples averaged, resulting in a 4 times smaller noise figure and better detection limit.

References

[1] DIN 55350–13: „Concepts in quality and statistics; concepts relating to the accuracy of methods of determination and of results of determination“

[2] ISO 5725–1 : „Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results – Part 1: General principles and definitions.“

[3] Haeri, H., Beal, C.E., and Jerath, K. (2021). Nearoptimal moving average estimation at characteristic timescales: An allan variance approach. IEEE Control Systems Letters, 5(5), 1531–1536. doi:10.1109/LCSYS. 2020.3040111.